Are Conspiracy Theories Inherently Irrational?

The belief common among intellectuals that “conspiracy theories” are inherently irrational or so unlikely as to be essentially inherently irrational is demonstrably false.

Merriam Webster defines conspiracy as “the act of conspiring together” and conspiring as “to join in a secret agreement to do an unlawful or wrongful act or an act which becomes unlawful as a result of the secret agreement.” The dictionary gives a range of word meanings for “theory” including “a hypothesis assumed for the sake of argument or investigation” which comes closest to the way “theory” is used in the phrase “conspiracy theory.”

The phrase “conspiracy theory” is used most often to mean “totally crazy conspiracy theory” or “conspiracy theory highly contradicted by the evidence” instead of the dictionary meaning of “conspiracy theory.” The phrase is often paired with “conspiracy theorist” and assertions that the conspiracy theory has been “debunked.” It is sometimes paired with the phrases “denier,” “denialism,” and “pseudoscience.” For example, “COVID denier” or “AIDS denier.”

“Conspiracy theory” is usually invoked to attack theories, evidence of misconduct, evidence of conflicts of interests, and even evidence of simple mistakes by authority figures in the group or groups — ethnic, professional, political, social — that the author identifies with or belongs to. In some case the author or authors using the phrase “conspiracy theory” are the subjects of the suspicions or evidence: https://thebulletin.org/2021/08/how-covid-19s-origins-were-obscured-by-the-east-and-the-west/.

“Conspiracy theory” is often invoked in discussions of murders or possible murders (suspicious “suicides” such as Jeffrey Epstein, accidents etc.) such as the assassination of President Kennedy or mass killings with actual or potential large scale political or economic consequences such as the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. A high percentage of “conspiracy theories” involve assassinations, mass killings, and other murders or possible murders. These include the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963, his brother Robert Kennedy in 1968, Martin Luther King in 1968, Malcolm X in 1965, US Senator Huey Long in 1934, the mysterious crash of TWA Flight 800 in 1996, the Columbine mass school shooting in 1999, the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the anthrax attacks just after the September 11 attacks in 2001 blamed on Bruce Ivins, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Conspiracy theory” is often paired with the explicit or implicit argument that “someone would have talked” and that an actual conspiracy could not keep its activities sufficiently secret to avoid prosecution or successfully organize a group, often implied to be large, of people covertly.

Conspiracy is recognized in common law and groups of people are convicted of conspiracy all the time. (UPDATE: August 29, 2021) See, for example, 18 US Code 371: Conspiracy to commit offense or to defraud United States

If two or more persons conspire either to commit any offense against the United States, or to defraud the United States, or any agency thereof in any manner or for any purpose, and one or more of such persons do any act to effect the object of the conspiracy, each shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.

If, however, the offense, the commission of which is the object of the conspiracy, is a misdemeanor only, the punishment for such conspiracy shall not exceed the maximum punishment provided for such misdemeanor.

Some recent conspiracy convictions found with the DuckDuckGo search engine on August 23, 2021:

https://www.justice.gov/usao-ma/pr/sutton-man-convicted-cocaine-conspiracy

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/man-convicted-conspiracy-import-and-distribute-fentanyl

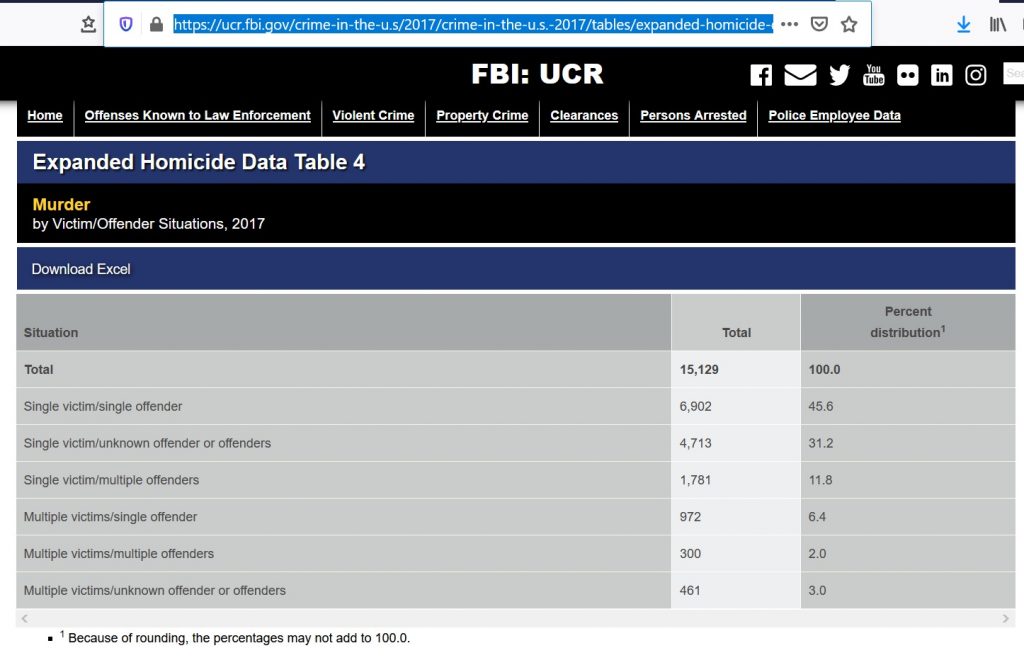

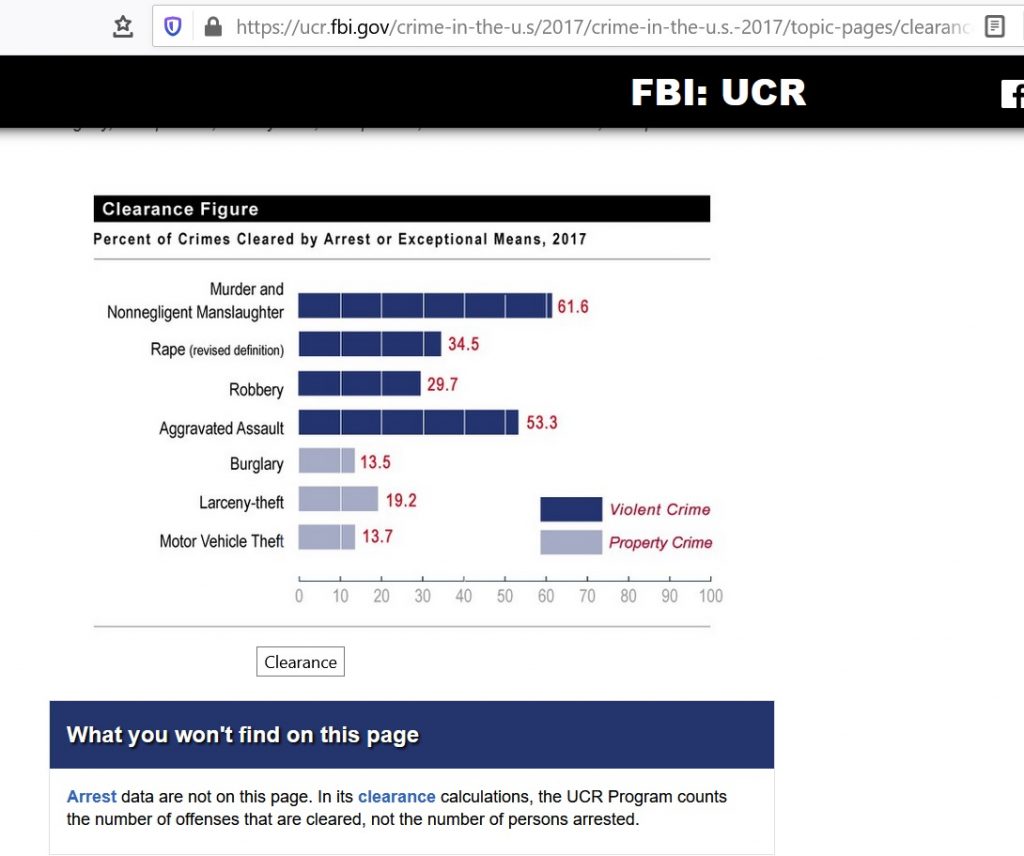

The US Federal Bureau of Investigation’s homicide statistics for 2019 attribute 14.7 percent of the total 13,927 murders that year to “multiple offenders,” meaning a conspiracy in common usage even if the case does not meet the legal definition of conspiracy or conspiracy was not charged for some other reason.

The same table attributes 27.8% of these murders to an unknown offender or offenders. This is particulary significant because a high proportion of unsolved murders in the United States are attributed to “gang violence” or “organized crime,” meaning a conspiracy in common usage.

UPDATE: August 29, 2021

See, for example:

Chen, Elsa Y. “Victim and Witness Intimidation.” Encyclopedia of Race and Crime. Editors Helen Taylor Greene and Shaun L.

Gabbidon. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications (2009)

Community-wide implicit victim and witness intimidation has become particularly severe and widespread in neighborhoods dominated by gangs and drugs, including many predominantly African American and Latina/o inner-city areas. Asian gangs also engage in intimidation. A well-known example of implicit intimidation is a grassroots campaign known as “Stop Snitchin’,” which began in Baltimore around 2004 and quickly spread to other urban areas by several means, including CDs and DVDs, websites, T -shirts, and rap lyrics. The movement’s purpose is to urge community members not to cooperate with criminal justice authorities, and to remind them that “snitches wear stitches.” Gang members have appeared in courtrooms wearing Stop Snitchin’ T -shirts, provoking efforts to ban the shirts by judges and political officials. The success of the Stop Snitchin’ movement can be attributed in part to some community members’ anger regarding the high rate of incarceration among minority men, frustration over criminal justice authorities’ use of informants from the community and jails or prisons to facilitate the prosecution and incarceration process, and general mistrust of law enforcement officials, who often do not provide adequate protection for those who do cooperate and sometimes reward unreliable informants with leniency in prosecution or sentencing. The Stop Snitchin’ mantra is redolent of the Italian Mafia’s centuries- old code known as omerta, an oath of silence prohibiting cooperation with the authorities under any circumstances.

The culture and attitudes surrounding rap and hip hop music have perpetuated the practice of victim and witness intimidation and the implicit code of silence . Some well-known rap artists have refused to cooperate in criminal cases in which they or their friends or members of their entourages were victims or suspects. Other popular rappers have produced songs urging listeners not to speak with the police. The murders of several rap and hip hop stars, including Tupac Shakur, the Notorious B.I.G., and Jam Master Jay from Run D.M.C., remain unsolved because of witnesses’ unwillingness to violate the “code of the street” by speaking to the police or testifying in court.

END UPDATE

“Over 1,000 victims, 126 dead, just 2 convictions: 6 years of mass shootings in Chicago” By Tom Schuba and Andy Grimm, August 2, 201, Chicago Sun Times

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/sep/04/chicago-gun-violence-unsolved-murders-deadly-year

Online searches for gang violence and unsolved murders often turn up articles and official reports using the phrases “gun violence” and emphasizing the race of both victims and suspected perpetrators of unsolved murders, usually in so-called “inner city” neighborhoods. Nonetheless careful reading show these articles and reports are talking about unsolved gang murders often involving drugs or other illegal activities: criminal conspiracies.

Some Famous (or Infamous) Unsolved “Organized Crime” Murders

Arnold Rothstein — November 6, 1928 — reputed prohibition era mob boss and “mentor” of Charles “Lucky” Luciano, Meyer Lanksy, and other famous mobsters.

Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel — June 20, 1947 — close associate of Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky

Albert Anastasia — October 25, 1957 — alleged mob boss and head of “Murder Inc.”

“Sam” Giancana — June 19, 1975 — alleged second in command of the Chicago Mob

“Johnny” Roselli — August 9, 1976 — alleged top figure in the Chicago Mob

Jimmy Hoffa — Teamsters Union Boss, disappeared July 30, 1975, declared dead July 30, 1982

John Favara — disappeared July 28, 1980, declared dead 1983, neighbor who disappeared after a car accident that killed mob boss John Gotti’s 12 year old son Frank Gotti. Favara was the driver of the car.

The history of organized crime in the United States is replete with many more unsolved murders and disappearances. In fact, people often don’t talk — at least not under oath in a court of law — and innocent witnesses often keep silent fearing retaliation from organized crime groups — conspiracies. Circumstantial evidence, suspicions, and rumors abound as is the case with murders such as the assassination of President Kennedy where the phrase “conspiracy theory” is invoked to ridicule and stigmatize those same sort of circumstantial evidence, suspicions, and rumors.

The empirical data from murder statistics and the history of murders is that criminal conspiracies are common — at least fourteen (14) percent of murders — and often escape successful prosecution. A high fraction of events where the phrase “conspiracy theory” is used to ridicule and stigmatize suspicions or even evidence of a conspiracy are also murders or possible murders: political assassinations, terrorists incidents, mass killings, suspicious accidents and suicides.

Are there high level international conspiracies?

High level international criminal conspiracies involving seemingly independent and even competing groups such as companies have been demonstrated in court in a number of cases.

Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Pfizer (yes the COVID vaccine company), and several other companies in Japan and Korea engaged in an illegal criminal conspiracy to fix the price of citric acid — a key ingredient of Coca-Cola and other sodas — and other food additives such as lysine in the 1990’s, probably beginning in the 1980’s or earlier. At this time, ADM and Pfizer dominated world production and sales of citric acid, an important and lucrative product due to its key rol in Coca-Cola and other sodas.

See for example:

https://www.justice.gov/archive/atr/public/press_releases/1996/1030.htm

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/3-540-34222-2_5

“Archer Executive Testifies to Fixing Citric Acid Prices” by Kurt Eichenwald, New York Times, August 13, 1998

“The Informant: A True Story” by Kurt Eichenwald, Crown, October 15, 2001

Rats in the Grain: The Dirty Tricks and Trials of Archer Daniels Midland, the Supermarket to the World, by James B. Lieber, Basic Books, January 10, 2002

Antitrust investigations have demonstrated several cases of international price fixing cartels for various products. Some price fixing arrangements are open agreements such as OPEC, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, and the proration of oil production in Texas by the Texas Railroad Commission. https://rrc.texas.gov/about-us/rrc-history/

Governments can and do provide cover, sanction, and legitimacy for price fixing arrangements that would be illegal and criminal otherwise.

Do Cartels Get Away with Illegal Price Fixing Agreements?

Some would argue that because ADM, Pfizer, and the other conspirators were caught, they did not get away with the crime and this somehow proves no one is able to get away with a criminal conspiracy. This, of course, is demonstrably not true for unsolved murders. In contrast to murders, where the crime is usually clear due to a dead body and signs of violence, proving a rise in prices is a crime — is due to a criminal conspiracy is inherently difficult.

There are a number of cases of mysterious increases in the price of various products and services, circumstantial evidence of price fixing and collusion as defined in antitrust law. A notable recent example is the remarkable increase in the price of insulin, a product produced in vats using well established genetically engineered bacteria. There is no obvious shortage of a key ingredient or other explanation.

See for example:

Despite widespread plausible suspicions, proof of an insulin price fixing agreement similar to the citric acid price fixing agreement remains elusive.

Another possible example is the marked rise in oil prices following a series of mergers of major oil companies in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s.

British Petroleum Amoco Merger: (August 1998): https://money.cnn.com/1998/08/11/deals/bp/

Exxon Mobil Merger (November 1999): https://money.cnn.com/1999/11/30/deals/exxonmobil/

Conoco Phillips Merger (November 2001): https://money.cnn.com/2001/11/19/deals/phillips_conoco/

Conclusion

Conspiracy theories are rational in many cases. Historical data on unsolved murders demonstrates that proving a conspiracy beyond a reasonable doubt is difficult however. Criminal conspiracies are NOT like laboratory experiments or astronomical observations. The belief common among intellectuals that “conspiracy theories” are inherently irrational or so unlikely as to be essentially inherently irrational is demonstrably false.

(C) 2021 by John F. McGowan, Ph.D.

About Me

John F. McGowan, Ph.D. solves problems using mathematics and mathematical software, including developing gesture recognition for touch devices, video compression and speech recognition technologies. He has extensive experience developing software in C, C++, MATLAB, Python, Visual Basic and many other programming languages. He has been a Visiting Scholar at HP Labs developing computer vision algorithms and software for mobile devices. He has worked as a contractor at NASA Ames Research Center involved in the research and development of image and video processing algorithms and technology. He has published articles on the origin and evolution of life, the exploration of Mars (anticipating the discovery of methane on Mars), and cheap access to space. He has a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and a B.S. in physics from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).